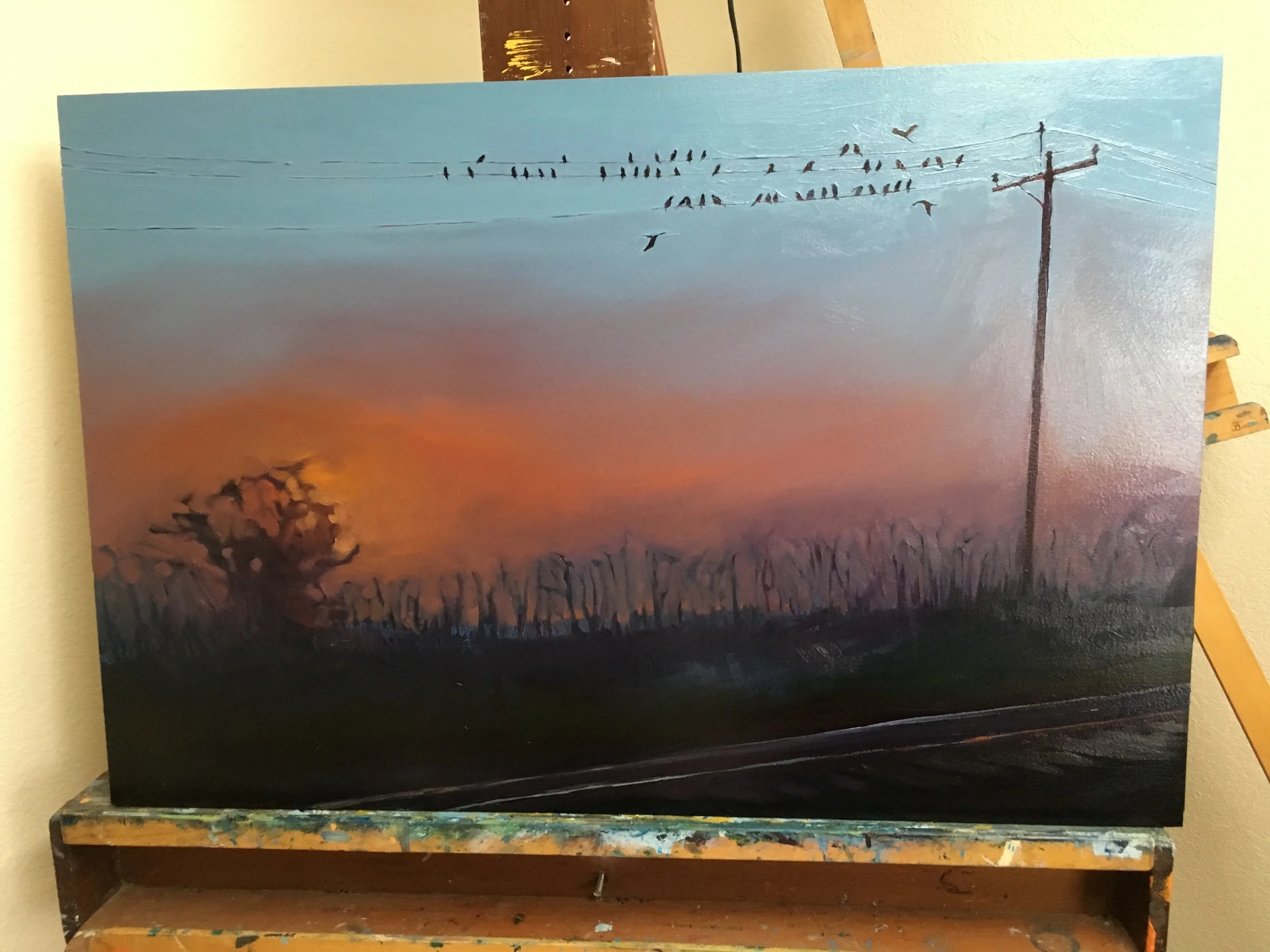

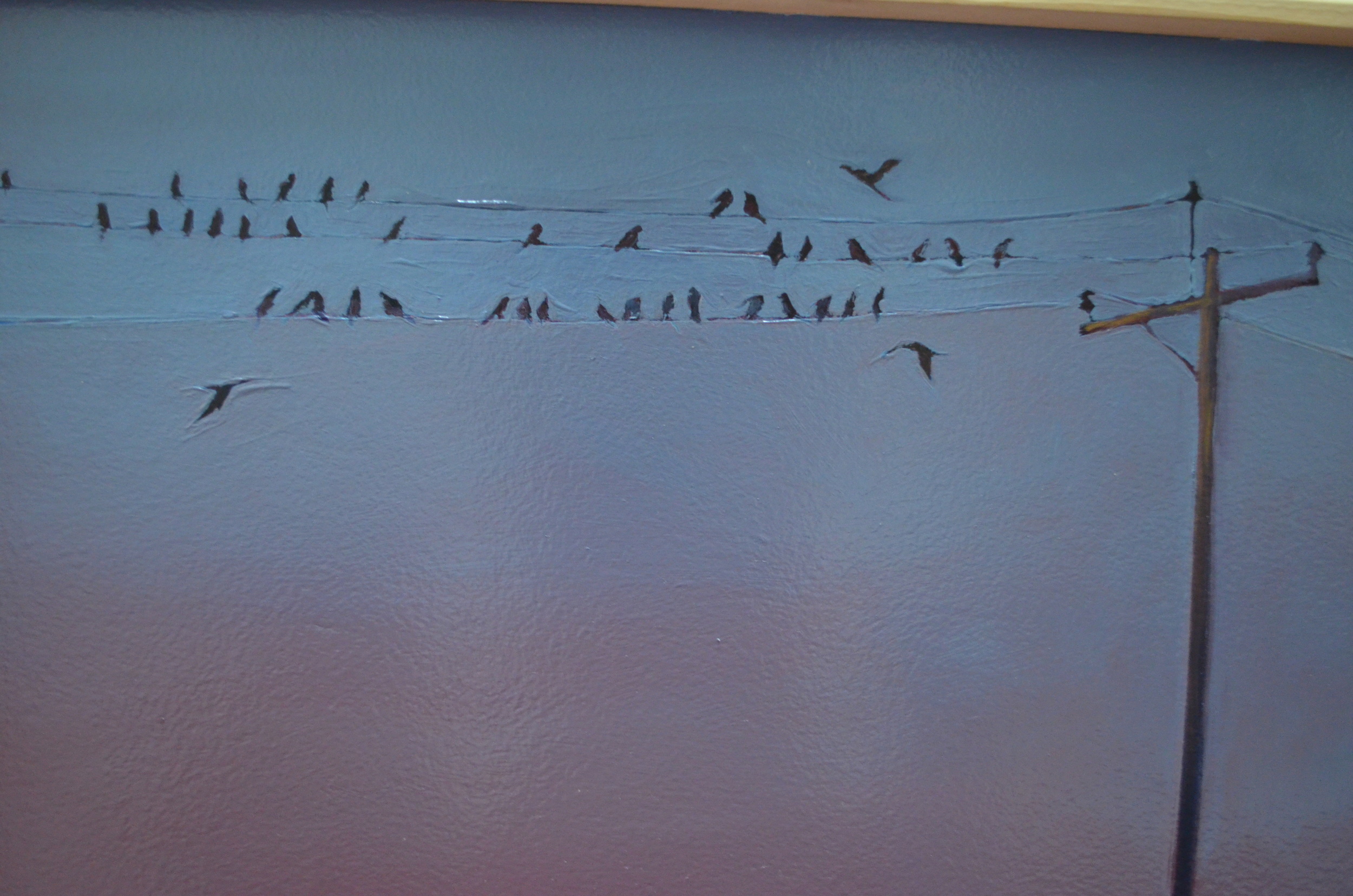

It's been over a year of painting a lot of wires and sun-related skies. Now, I'm ready to do some naked people. I mean, ready to paint them. I mean ready to paint images OF them. And a few other ideas are in my mind. It's not that I feel that I've conquered the wire + sky business, but more a matter of needing new scenes. "As the world turns", I'll be exploring similar ideas but with new images. That's all it will come down to most likely. But last week I found myself sweating under my hair net trying to whip up another batch of dawn/dusk and protruding pole combo with trees on the side. Not to say there wasn't joy in yea ol' journey, but working on this piece took some particular, peculiar concentration. It's a curve ball thrown in the game to do something I love, but with ambivalence. Maybe like agreeing to a coffee with an old sex-object?

I've already told you about reading "The Painter". Here I offer an excerpt from a scene in which the main character, Jim Stegner, a professional painter and his girlfriend are considering the "trend" of southwestern paintings that typically include blue coyotes. This scene speaks to my current feeling about having painted wires and sunrises/sunsets for over a year. It also illuminates a bigger idea of why I think some things/relationships/stories/images work and others do not: our ability to empathize. Finally, I like this passage because I simultaneously nod along with Jim and laugh at him along with Sofia, his girlfriend. She starts off here:

"Look, look you big lug. This one. Stand here. No, here. Close you eyes. Now imagine there had never been a blue coyotes in the world. There was water, there was darkness, there was the Void, and then the Word and then there was a blue coyote! Voila!"

She poked me. "You can open your eyes now."

"Oh, sorry."

She was sort of right. To me. It was a good painting. That's probably how it happened for Heberto Nunez-Jackson. He painted the first one out of the Void and it was really compelling and he did it again and it was also pretty good and he got addicted to that relationship with Creation: him, the darkness, the coyote, blue. And the red moon broke his own heart one day. I got it. And then you have a habit and all you ever wanted in the world was to feel this thing about what you create, and then presto your coyote paintings begin to sell like hotcakes. And the people in the ski lodges and big adobe houses who buy them don't really care if their blue coyote has a hundred cousins, maybe they actually like it, it makes them feel part of a trend, a phenomenon in art that is repeatedly reinforced. And so everybody is happy.

"What do you think?" she said, standing before [the painting] and gesturing with her hand like a game show model. "The only, the first. Look! The composition, the color. It's really good. How is it different than a thousand of your Diebenkorn Ocean Park paintings?"

I looked.

"It just is."

"Ohhhh, snobbism. I never, ever thought I'd see that in Jim Stegner."

"Not a snob. I believe in truth. Which is also excellence, by the way."

She narrowed her eyes at me. "You mean raw, clumsy honesty is the same as excellence?"

"I didn't say that. Truth needs excellence. Honesty is not the same same truth."

"Huh." She frowned, willing, maybe, to give me the benefit of the doubt for at least a split second.

"Truth needs honesty, but that is not all it needs."

"Speak."

"Well, an artist can be honest in her rendition of say a hummingbird, in how she sees it, in her application of technique, but she may not be true to the bird."

"You mean in skill?"

"In skill, in her ability to see. To really see the bird. To see the bird as it bears its spirit forward into the world. In empathy. When all of that is there you can feel it. It knocks you over."

"Huh."

"There is something in even this coyote, this dawn of the world Genesis coyote, that is not true. He did not see into the heart of the coyote. And so I reject it. That is not snobbism."

"Huh." She smiled at me. She said: "He speaks, who knew? He's sort of a guru."

"You didn't think I had opinions on art?"

"Pretty much I just saw you as a sex object," she said.

"Hah!"

Heller, Peter. The Painter. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014. 229-230. Print.